De Achttiende Eeuw 41 (2009) nr.1

Themanummer ‘Maskerade en ontmaskering’

Eveline Koolhaas-Grosfeld, Verklaring der plaat

C. Troost, Arlequin, tovenaar en barbier: de bedrogen rivalen, 1738 Mauritshuis, Den Haag

Zoals er altijd mensen zijn die plezier beleven aan maskerades, zo zijn er ook altijd mensen die dat plezier veroordelen. Die verschillen vind je op achttiende-eeuwse uitbeeldingen van maskerades in allerlei vormen terug. Uitbundig plezier spreekt uit de even illusionistische als surrealistische fresco’s op de muren van de Maskerade Hal van het kasteel Cesky Krumlov (Tsechië), in 1748 geschilderd door Josef Lederer; zijn levengrote, vermomde figuren maken de toeschouwer als het ware deelgenoot van het feest. Bij Pietro Longhi daarentegen, specialist in het schilderen van de gemaskerde Venetiaanse aristocratie, bekijk je dat gedrag meer van een afstand. Longhi’s werk heeft soms een kritische ondertoon, maar dat is niets vergeleken bij de scherpe veroordeling van maskerade en bedrog in de serie Los Capricos van Francisco Goya. Hij spreekt de mensen ook aan op het gemak waarmee zij zich laten bedriegen. Het tegenovergestelde vertelt een academisch historiestuk als dat van Gerard Lairesse, Achilles wordt ontdekt tussen de dochters van koning Lycomedes, een thema uit Ovidius’ Metamorphosen. Dit schilderij gaat juist over een geslaagde ontmaskering. Het toont de jonge Achilles, vermomd in vrouwenkleding om aan de strijd tegen de Trojanen te ontkomen, op het moment dat hij zijn sexe verraadt door uit de mooie spullen die Odysseus (als koopman verkleed) de koningsdochters komt aanbieden, direct het zwaard te kiezen. Hoe weinig subtiel is hierbij vergeleken de Arlequin van Cornelis Troost, het beeld dat als blikvanger voor het maskerade-congres van 2008 was gekozen. Anders dan bij Lairesse (waar je niet direct ziet dat de hoofdfiguur geen vrouw is), ligt de vermomming van Arlequin als ‘chirurgijn à la mode’ er duimendik boven. De klucht van Willem van der Hoeven uit 1730, waar Troost deze scène op heeft gebaseerd, is al net zo doorzichtig. De twee ‘rivalen’ die door Arlequin onder handen worden genomen zijn Belloardo en Capitano; zij dingen met instemming van Pantalon naar de hand van zijn dochter Sofie. Maar Sofie houdt van Antonio en Antonio van haar. Als dienaar van Antonio bedenkt Arlequin een list. Zich uitgevend voor Waalse choiffeur met ervaring aan het Franse hof, takelt hij de twee rivalen zodanig toe – ‘hij smijt ze met nat meel over de tronij, en stopt ze elk een bak wol over ’t hoofd’ – dat ze door iedereen worden bespot. Het slot laat zich raden. Pantalon voelt zich misleid en bedrogen, Antonio krijgt Sofie. Al is dit soort humor niet meer van deze tijd, de barbiersscène van Troost blijft aanstekelijk.

- voor Lederer: www.castle.ckrumlov.cz, geraadpleegd 29 april 2004.

- voor Lairesse: catalogus De kroon op het werk. Hollandse schilderkunst 1670-1750, tentoonstelling Dordrechts Museum (Dordrecht 2007) 172-173.

- M. Craske, Art in Europe 1700-1830 (Oxford 1997) 145-174.

Kornee van der Haven en Eveline Koolhaas-Grosfeld, Maskerade en ontmaskering: een inleiding

Herman Roodenburg, Tranen op het preekgestoelte. De achttiende-eeuwse kanselwelsprekendheid tussen toneel en authenticiteit

During the eighteenth century pulpit oratory underwent some major changes. After the middle of the century treatises on the subject brought aspects of actio or pronuntiatio to the fore and advised preachers to not only address the minds of the faithful but also their hearts. In the process, pulpit oratory found a welcome ally in the contemporary culture of sensibility and in various Pietist variants. In this article, the new affective oratory is explored in its English, German, and especially its Dutch developments. Partly patterning itself on the bodily eloquence of actors, it also condemned their actio as deceitful and inauthentic.

Theo van der Meer, Demasqué van het weten. Seksuele ontologie en homoseksualiteit ten tijde van de Republiek

For centuries masquerades and homosexuality have been closely associated. From the moment homosexuals developed an identity, ‘wearing a mask to hide their true selves’ had become part of common parlance among them. ‘The mask’ preceded the American expressions about being in or out of ‘the closet’ that started to be used also in Holland in the 1970’s. In early modern Holland a different kind of masquerade existed that was less literal: until early modern Europe’s most violent outburst of persecutions of so-called sodomites occurred in the Dutch Republic in 1730, homosexual behaviour was supposed not to exist in this country. The denial was part and parcel of a sexual ontology that not only explained eroticism and gender in a religious context, but also accounted for the prominent place the Republic held in the world. Any disruption of this ontology, in the words of Erving Goffman, was dealt with backstage, through secret executions and the destruction of records. Even while the public at large knew better, until the discovery of a nation-wide network and subculture of sodomy, the myth of the non-existence of same-sex behaviour in the Republic was maintained to uphold the existing ontology. Only the discoveries of 1730 put sodomy in the spotlight and changed the roles of all involved, including the audience, which from then on was to witness public executions of sodomites. Especially these executions generated new meanings and a new ontology, which in time required more literal forms of masquerade for those who desired their own sex.

Jeroen Duindam, Het vroegmoderne hof als maskerade

‘Masquerade’ not only literally means disguising or ballet in disguise; it also indicates camouflaging intentions or emotions. This essay discusses the relevance of both meanings for the early modern court – putting into perspective the literary reputations of the court, while at the same time providing an analysis of dressing up at court from Reformation to Revolution.

Courts have traditionally been seen as places where dissimulation and intrigue dominated. This critical approach intertwined with a literary tradition that idealized the court as centre of suave manners and easy sophistication. Courtier and anti-courtier literature alike conveyed an image of the court that stressed control of impulses and a detached approach to social interaction. This could easily be read as cynical behaviour, akin to Machiavelli’s portrayal of the Renaissance prince. Machiavelli and Castiglione reinvigorated the age-old debate on the morality of rulers and courtiers. Their works occupied centre stage when religious strife swept across Europe. Politico-religious upheaval created an atmosphere of intense distrust, labeled an ‘age of dissimulation’ by Perez Zagorin.

In recent years, the study of courts shifted its focus from published literary sources to archival materials; this reorientation underlined the simple every day patterns in princely households. Isolated highpoint, taken up in Rulers’ propaganda and embellished in literary responses, have too long obscured the down to earth realities. Among court festivities the phase of disguising and dressing-up from Epiphany to Ash Wednesday occupied an important place. Typically these masquerades included the social antithesis of courtiers: shepherds, peasants, inn-keepers, artisans. The cast of the meals, dances and ballets involving disguises was carefully determined: the hierarchies were as a rule conspicuously visible even if they reverted daily practices. The eighteenth-century opening up of courts, mixing court and city in bals masqués and ridotti, did not fundamentally change this pattern.

Late eighteenth-century critique reiterated the old moral complaints about the court in more vehement form. Interestingly, the French Revolution, ousting the king and his court, also forbade carnival and the wearing of masks. Both elite politesse and popular carnival were seen as inappropriate for the true patriot.

Tanja Holzey, Morele en immorele’ maskerades in de toneelstukken van Nil Volentibus Arduum

This article aims to demonstrate the didactic use of masquerardes in the theatre plays of the early modern Dutch art society Nil Volentibus Arduum (Nil). It will show and explain significant differences between the use of masquerardes in comedies and tragedies. Furthermore the article will discuss the influcence of poetical and philosophical ideas on the composition of the character in the plays of Nil as well as the diverse forms of masquerade that accompany the different kinds of character types.

Jan Rock, ‘De Ezel die een Leeuwenhuid aangedaan hadt.’ De ontmaskering van Klaas Kolijn en de Nederlandse filologie (1709-1777)

The chronicle of Klaas Kolijn pretended to be a thirteenth-century account of the history of the counts of Holland, but it was a forgery. Written around 1700 by Reinier de Graaf, it was held genuine until as late as 1777. This article tries to explain why the forgery was able to confuse serious scholars during three quarters of a century. It looks for answers in the history of Dutch philology, in the aims of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century antiquarian research and in contemporary epistemologic theories of probability. The debates on Kolijn were held on three moments throughout the century. Around 1710, Kolijn’s text was edited for the first time, as it fitted perfectly in an antiquarian quest for more knowledge on the earliest history of Holland. Around 1745, debates on Kolijn shifted the focus from the text itself to its constitutional consequences and to the epistemological and moral reliability of the scholars Gerard van Loon and Pieter vander Schelling, who edited and studied Kolijn. Finally, in the 1770s, Balthasar Huydecoper focused back on Kolijn’s text, ascertaining with linguistic arguments that it could not be written at the time it pretended. The final argument discrediting Kolijn, brought up by historian Jan Wagenaar at the learned society of the Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde, was the absence of an old manuscript. Thus, Wagenaar transferred an old antiquarian epistemological requirement of material evidence to the Dutch philology, newly organised in a learned society.

Wiep van Bunge, Geloof, geluk en (de angst voor) chaos [recensieartikel]

De Achttiende Eeuw 41 (2009) nr.2

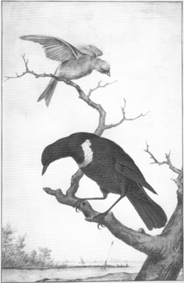

Eveline Koolhaas-grosfeld, Verklaring der plaat

Aart Schouman (Dordrecht 1710 – 1792 Den Haag). Aquarel (418 x 267 mm) met aan de achterzijde in potlood het opschrift ‘Een Canarie Vogel en Ring leijster. Levensgroot’

De geschilderde vogelwereld van Aart Schouman (1710-1792) behoort tot het mooiste wat de Nederlandse achttiende-eeuwse kunst te bieden heeft. Ook zijn tijdgenoten waren een en al lof over zijn aquarellen: ‘Schouman trof niet alleen de edele en bevallige gestalte der vogelen, maar de schoonste kleuren waar mede de grote Schepper van alles hunne vederen versierd heeft, wist hij, op de leevendigste wijze, naar ‘t leeven af te malen’, schreef Cornelis Ploos van Amstel. Voor deze gerenommeerde kunstkenner (en vast niet alleen voor hem) was de bewondering voor Schoumans natuurgetrouwe kunst tegelijk een eerbetoon aan God.

Schouman was gewend al het soort werk aan te nemen wat er voor een achttiende-eeuws kunstenaar maar te doen was – het schilderen van behangsels, portretten, wijzerplaten, raamhorren en glaasjes voor de toverlantaarn – tot hij als bekwaam kopiist van oude schilderijen toegang kreeg tot de huizen van kunstverzamelaars. Daar kwam hij in aanraking met nog een liefhebberij van de welgestelden: het houden van vogels. Schouman zag een gat in de markt en ontwikkelde zich tot een zeer gerespecteerd specialist in de vogelschilderkunst. Met name van stadhouder Willem V kreeg hij volop de gelegenheid om de beestjes te bestuderen, in levende lijve in de vorstelijke menagerie, of in opgezette vorm in zijn naturaliënkabinet. Schouman las ook boeken over de natuurlijke historie, vertellen de kunstenaarsbiografen Van Eijnden en Van der Willigen. Op de aqarellen vinden we daar iets van terug in de met enkele fijne penseelstreken aangeduide kenmerken van de landstreken waar de vogels zich in het wild ophouden. Bij de hier afgebeelde kanarie hoort dus eigenlijk een exotisch oord, maar kennelijk vond Schouman zijn soort ingeburgerd genoeg om hem samen met een ringlijster tegen een Hollands watergebied af te beelden.

- C. Ploos van Amstel, ‘Schets van het leven en de verrigtingen van den Heere Aart Schouman als kunstschilder beschouwd’, Algemeene Vaderlandsche Letteroefeningen (1792) 432-439.

- R. van Eijnden en A. Van der Willigen, Geschiedenis der vaderlandsche schilderkunst, II (Haarlem 1817) 68-73.

- L. J. Bol, Aart Schouman: ingenious painter and draughtsman (Doornspijk 1991).

Wijnand Mijnhardt, Foreword

Jonathan Israel, Equality and Inequality in the late Enlightenment

Wiep van Bunge, The Modernity of Radical Enlightenment

Joris van Eijnatten, What if Spinoza never happened?

Wyger R.E. Velema, Jonathan Israel and Dutch Patriotism

Jonathan Israel, Toleration, Spinoza’s ‘realism’ and Patriot modernity: replying to Van Eijnatten, Van Bunge and Velema

Tom De Roo, Kanarieliefhebberij in de achttiende eeuw – op het kruispunt van wetenschap en vrije tijd?

This article argues how eighteenth-century canary-curiosity sits firmly on the crossroads of science and leisure, with both aspects joined together through commercialisation. The word ‘curiosity’ denotes a healthy scientific interest in the intricacies of the natural world, this being both an early modern tradition and an enlightened ideal. In addition, the early eighteenth-century literary sources on canaries show a certain scientific value in their methods and digressions. Yet there is also ample evidence for the leisure element through references to recreational benefits as well as affinities with ‘typical’ leisure activities.

The specialised literature offers as wide a public as possible an easy way into the keeping of canaries. This democratisation of canary-curiosity serves to make money for a variety of retailers: it is commercialisation that links science to leisure. Firstly, the printers and authors of canary-literature ride on an ever expanding wave of popularised books on science and leisure, offering knowledge for sale at a broad range of prices and of varying quality. The canary-literature evolves accordingly: from a small number of thick and thorough works at the start of the century, to a larger number of smaller, cheaper and ever more superficial booklets and sections in all-round leisure books towards the 1900s. Secondly, retailers of bird paraphernalia and professional breeders – though often loathed as being ‘not really curious’ – offer every possible element required by the average person to start his or her canary-fancy, from cheap and common birds and cages to exclusive canary varieties and conspicuous birdhouses. Authors/printers of canary-literature and sellers of birds and accessories are sometimes even the same people, thereby ensuring that literary communication promotes commercial business. ‘Do-it-yourself’ is put forward as a legitimate way into the canary-curiosity for the less affluent or the passionate amateurs, although it only applies to some aspects and thus still requires professional providers for what one can’t produce oneself.

The increasingly professionalised leisure-oriented market undoubtedly satisfies a demand engendered by an enlightened interest in nature, but it also increases it through a lowering of the material and socio-cultural thresholds for the keeping of canaries. This particular evolution typifies the eighteenth century as a time of intensifying commercialisation. It appears to allow an ever expanding group of people to come into contact with popularised knowledge. Its influence on the democratisation of leisure and science and their intertwining should not be underestimated.

Matthias Meirlaen, Het verhaal van de moraal: universele en nationale geschiedenis in de Zuid-Nederlandse colleges na de Theresiaanse onderwijshervorming (1777-1789)

Much earlier than elsewhere in Western Europe, history appeared as a compulsory, autonomous subject in the secondary school curricula in the Southern Low Countries. In 1777, during the Austrian regime, a national educational reform prescribed the education of history in every secondary school. According to the programme of this reform, the history course had to contain lessons of both universal and national history. In this article, the relation between these two types of history is discussed. First of all, the different historiographical traditions of universal and national history are examined. Secondly, the narratives of the recommended textbooks are compared with one another. And finally, the way teachers dealt with universal and national history in everyday school practice is explored. Concerning the latter, this article especially wants to prove that, despite their different narrative traditions and schemes, universal and national history were closely connected in the classroom. In the eyes of the teachers, both had to be instructed in order to train the pupils’ moral.

Tanja Simons, ‘Ik heb ook nu niet uijt mij alderbest geschreven.’ Achttiende-eeuwse brievenboekjes en de gekaapte brieven van Aagje Luijtsen

In the 18th century the Netherlands experienced a boom in all kinds of educational literature. Among these were so-called correspondence manuals, small books that gave instructions on how to write personal letters and provided models of them. Up till now it was not quite clear for whom these manuals were intended. However, it is known that in the highest ranks of society epistolary etiquette was passed on from generation to generation. So perhaps these books were mainly meant for and used by the middle and lower classes. This article gives a short description of five such manuals (and one related to the genre). Subsequently twenty letters, written between 1776 and 1780 by a young woman called Aagje Luijtsen, are examined for traces of the rules provided by the manuals. Furthermore the opening and closing formulas that Aagje uses in her letters are compared with those that are used in the model letters.

Matthijs Wieldraaijer, De sensibele stadhouder en de gedisciplineerde gouvernante. Beelden van Willem IV en Anna van Hannover in preken.

When William IV of Orange died in 1751 and his wife Anne of Hanover in 1759 they were both eulogised by a great number of Reformed ministers from the pulpit. In this article images of William and Anne as they appear in these funeral sermons will be analyzed. In the following I have confined myself mainly to the role gender played in selecting the virtues ascribed to the deceased by the Reformed clergymen. I will argue that due to changing conceptions both of stadholderate and of masculinity and femininity, William is portrayed as a sensitive, well-educated bureaucrat and Anne as a sensible, talented and disciplined mother and stateswoman.

Je moet ingelogd zijn om een reactie te plaatsen.